What are Web Applications?

Origins, motivations and current context of these essential components of the modern Internet

You've probably heard of it. Or maybe not. Either way, you deal with it every day. Right now, you're interacting with a web application, the one that generates the pages of this site. In this article, we'll look at what it is and why web applications are so important today.

The origins

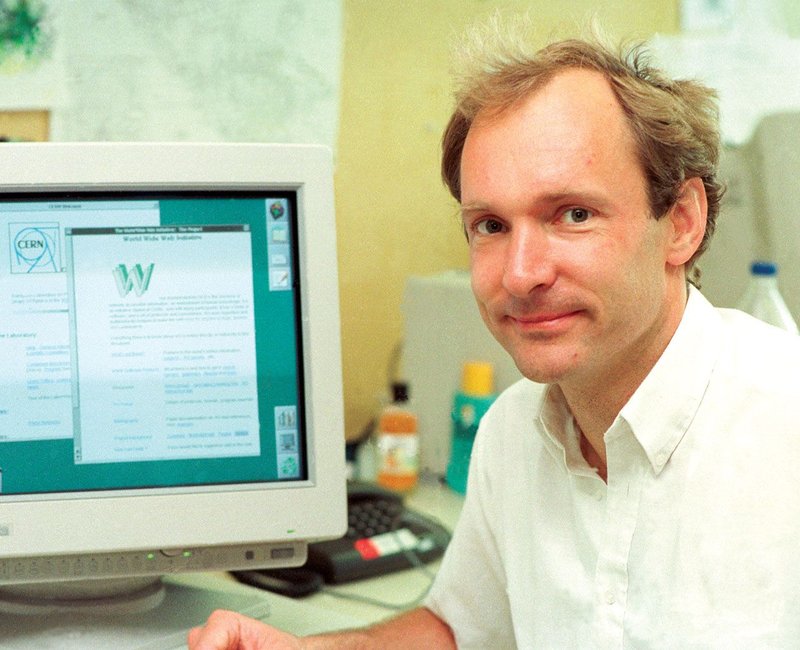

The World Wide Web (WWW - literally translated as global network , or more simply web) was invented by Tim Berners-Lee in 1989 at CERN (European Council for Nuclear Research, see cover image), today the most important research center in the world for the study of elementary particles.

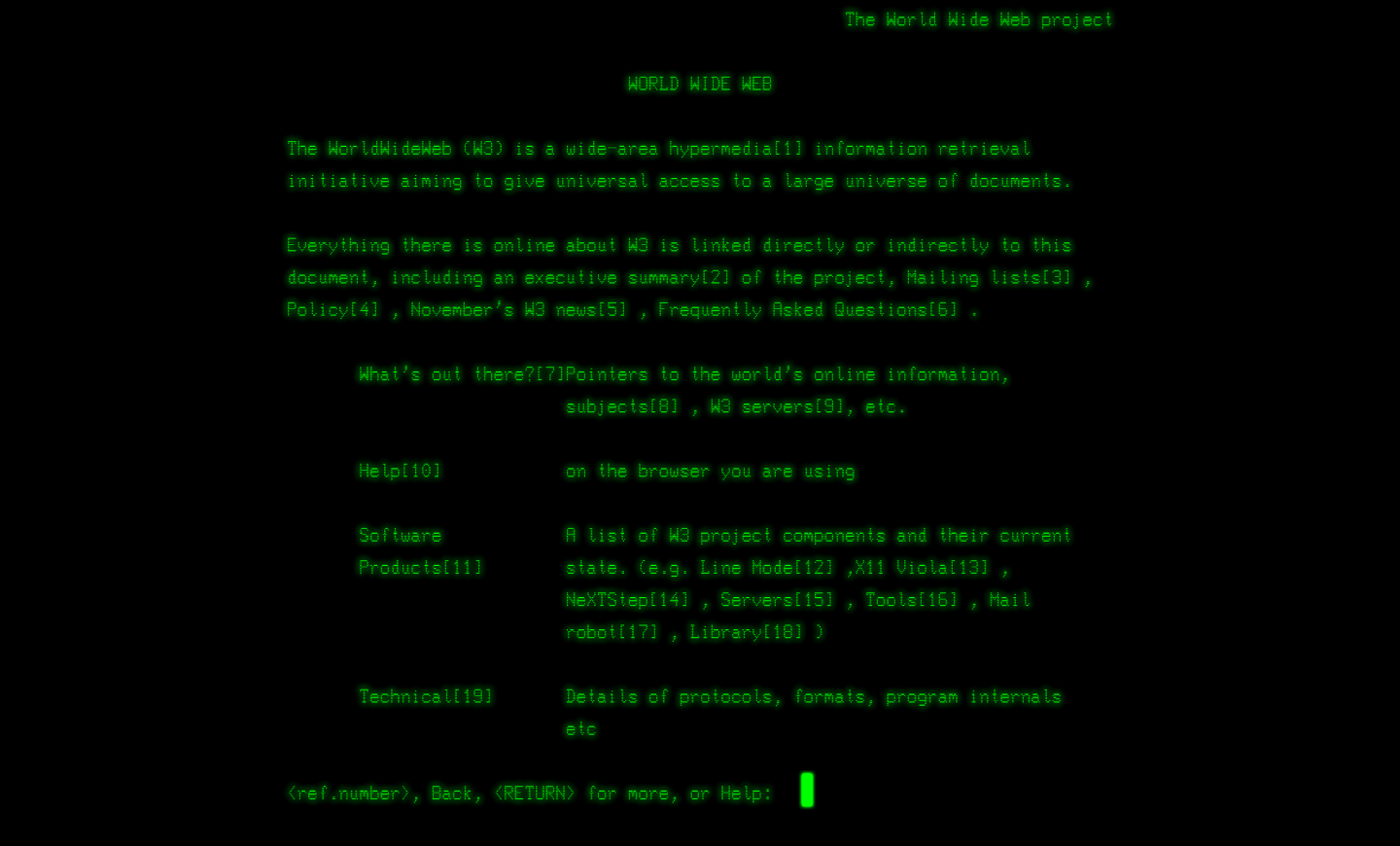

The web was primarily a response to the need for information sharing in research. CERN could have patented the idea, but it didn't. Instead, in 1993 it released the web under a public license (see the figure below), simply retaining its intellectual property. This decision marked the beginning of a revolution that continues to this day.

The main mechanism

The web is a distributed system for exchanging documents and information, based on a client-server architecture. The server is a constantly active system, typically accessible remotely (via the Internet), waiting to be queried. The client, on the other hand, is a system capable of querying the server and retrieving responses containing the requested information.

The communication language is established by a standard protocol (HyperText Transfer Protocol - HTTP), currently available in three main versions (HTTP version 1.1, 2, and 3) as specified in the "Request For Comments" (RFC 9110). In modern web systems, communication is increasingly bidirectional and asynchronous to support interactive features. In particular, after an initial "discussion" in HTTP (technically called a handshake), the server can send data without any explicit client request (e.g., to send real-time notifications) through standard protocols such as WebSocket (RFC 6455).

In modern implementations, as a good security practice, the exchange of messages takes place within an encrypted channel that protects the confidentiality of the information and allows the client to authenticate the server, through a lower level transport protocol (Transport Layer Security - TLS, latest version 1.3 - RFC 8446).

Web applications

Originally, the web was essentially an archive of static documents (files) hosted on servers, freely accessible to anyone. Updating the information in these documents was typically the responsibility of system administrators themselves. The need for flexible mechanisms for entering and retrieving information led to the creation of so-called web applications, which are programs capable of processing, storing, and displaying information exchanged between clients and web servers.

Nowadays, web applications are the de-facto standard for building services and user interfaces on the Internet (even apps on your smartphone!)

Modern web applications are highly complex programs because they rely on a wide range of client- and server-side interpreters, at varying levels of abstraction and located on the network. The executable code is often distributed across multiple servers, belonging to different networks and organizations. It is therefore difficult to precisely define its scope. Furthermore, the input/output, programming languages, and technologies used are extremely varied.

A concrete example

For example, let's see what happens when you enter a search term (e.g., world wide web) into your browser or a favorite search engine widget (e.g., one based on WebKit) on your smartphone. In this case, the system will contact an address like: https://www.google.com/search?q=world+wide+web.

Your client (browser) will perform three main operations at different levels of abstraction:

- Identify the IP address corresponding to the domain name www.google.com (by requesting the Domain Name System – DNS);

- Activate an encrypted communication channel (TLS) with the web server listening on the identified IP address;

- Send an HTTP request message "GET /search?q=world+wide+web" over the encrypted channel.

And on the server...what happens?

The request message is interpreted by Google's web server to determine which program to run (web application associated with the /search path) and what input to send to it (variable q=world+wide+web note: spaces are encoded with the + sign).

Running the /search web application outputs text encoded in Hypertext Transfer Markup Language (HTML) that is sent back to the browser through the encrypted channel.

What happens now in the browser?

Client-side HTML content interpretation automatically triggers:

- further requests on other web addresses/resources;

- interpretation of content in another format:

- Binary like images or videos;

- Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) to determine the look and structure of the interface;

- JavaScript to make the user interface interactive;

The interpretation of CSS, and especially JavaScript, can in turn lead to new requests to additional web addresses/resources. JavaScript is, in fact, the de facto standard for implementing the client components of web applications (code executed on the client, rather than the server).

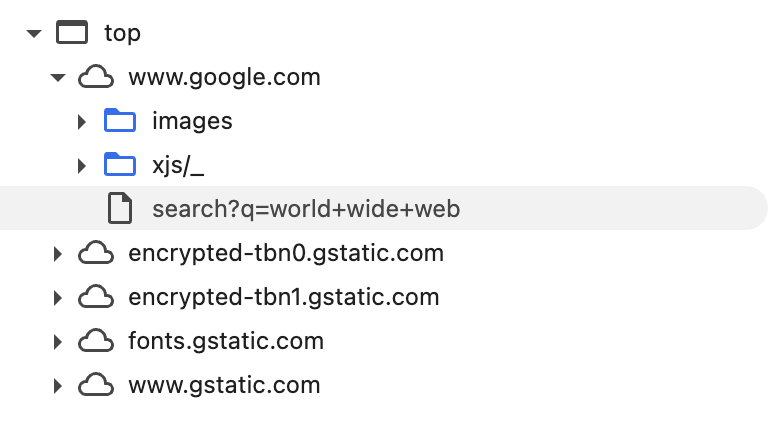

Consider that the single previous search generates a cascade of over 50 requests to servers associated with Google. The following figure shows a hierarchical view of the servers (different domain names associated with each cloud icon) contacted as part of this single request.

Note that the requests involve servers/domain names which are different from the originating one. This is a typical case, given the distributed nature of modern web applications. A unique aspect of our example, however, is that all the servers are traced back to the same organization (Google, or more precisely, the holding company Alphabet Inc).

In a typical web application available on the Internet, associated requests involve organizations other than the one associated with the initial domain name, in a way invisible and transparent to the user.

Well, guess what? It's been estimated that 80% of web services on the Internet use resources associated with Google (which can therefore track your activity, regardless of whether you use its services or whether the service provider explicitly uses Google for user tracking). In this situation, there are countless ways Google can track user behavior. The most straightforward method is to look at a request header field called Referer, typically include in every request by web browsers, which identifies the address of the web page from which the resource has been requested.

In future episodes, we'll explore methods for improving our privacy on the web. For now, I hope I've provided you with some key information to understand what web applications are and how central they are to the modern Internet.

Find more blog posts with similar tags